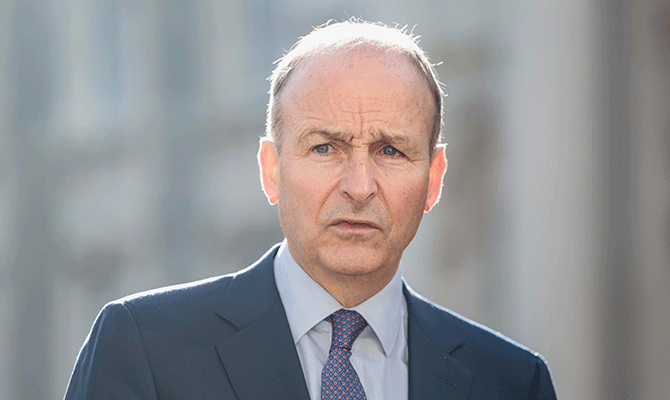

Micheál Martin

MICHEÁL MARTIN’S move to legislate for the abolition of the triple lock could run into political, constitutional and even EU legislative trouble, judging by statements uttered by Martin himself and intergovernmental declarations made to facilitate a ‘yes’ vote in two EU referendums. The Dáil heard Sinn Féin’s Pearse Doherty remind Martin last November that a decade earlier he had defended the triple lock, telling the then Fine Gael/Labour coalition government: “The current policy works and it has complete popular legitimacy. There is no reason whatsoever to change it. Such a change will impress no one in Europe and it will contribute nothing to international peace. Instead of sniping at our neutrality, the government should acknowledge what we have achieved because of it and set out a policy to strengthen rather than to undermine it.” Sterling stuff, but then Martin was in opposition at the time.

However, Doherty also reminded Martin that the programme for government signed up to by the Fianna Fáil leader when negotiating to get into Government says: “The Government will ensure that all overseas operations will be conducted in line with our position of military neutrality and will be subject to a triple lock of UN, Government and Dáil Éireann approval.” That statement is equally strong and very clear about the link between neutrality and the triple lock.

The real problems about abolishing this safeguard, however, may be far more compelling than Martin doing political somersaults and could involve all sorts of legal actions at home and abroad. Goldhawk is indebted to Anthony Coughlan, a seasoned campaigner against EU federalism and various treaties designed to create same, for his analysis of what Martin’s proposal means for EU treaties voted on in the past.

Coughlan points out that a national declaration issued by the Irish government at the 2002 Seville European Council meeting induced Irish voters to support ‘yes’ to the ratification of Nice Treaty 2, having rejected Nice Treaty 1 the year before. The declaration said that Irish Defence Forces’ participation in overseas operations abroad requires “(a) the authorisation of the operation by the Security Council or the General Assembly of the United Nations, (b) the agreement of the Irish government, and (c) the approval of Dáil Éireann and in accordance with Irish law”.

The European Council then declared that it “takes cognisance of the National Declaration of Ireland” and that Ireland intends to associate this declaration with its ratification of the Nice Treaty should the referendum be passed – which it was, on the assumption that this declaration was genuine. When the Lisbon Treaty was rejected, its second iteration in 2009 involved the referendum commission, chaired by Mr Justice Frank Clarke, sending information to all voting households. This included a reference to the declaration (quoted in the enclosed information booklet) on the triple lock, saying it “will be associated with the instrument of ratification if Ireland does ratify the Lisbon Treaty”.

Anthony Coughlan

This the Irish people did, given once more a trusting electorate that believed the assurances of the government, which included Martin at the time. Recent commentary on Irish foreign policy, neutrality and the triple lock (the latter underpins neutrality) is driven by the western states, Britain and the EU’s main powers. The West sees China, Russia and other emerging rival powers as the enemy and as a bloc that will have to be confronted militarily. Irish complicity would hardly make much difference to the balance of military forces across the globe but our credibility as a non-aligned, neutral country would, if we could be persuaded to join up, be a symbolic victory for the generals and the industrial military complex in the West.

However, the accompaniment of the triple lock declaration in the two EU treaties mentioned above and the clear impact it had on both referendum ‘yes’ votes, is very likely to provoke legal and constitutional actions by individuals or parties. And just what does the government think President Michael D Higgins will do when asked to decide whether to refer the constitutionality of a bill to abolish the triple lock to the Council of State? Can we expect another referendum, this time on a subject – neutrality – for which the polls have repeatedly shown there is much support?