Keir Starmer

It’s now universally accepted that the British don’t keep treaties and certainly not the parts that don’t suit any incoming government, like the Conservatives in 2010. This dishonourable behaviour isn’t new: Britain wasn’t known as ‘perfidious Albion’ for nothing. In the 1950s Charles De Gaulle complained: “For England there is no alliance which is binding, no treaty which is honoured, nor any truth which counts.” He knew what he was talking about having been misled and double-crossed from 1940-47. How long will it take Irish governments to cop on? For years the British have been in flagrant breach of important parts of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA).

The agreement enjoins the sovereign power in the north to behave with “rigorous impartiality” towards both main communities. After all, decades of discrimination and exclusion of the nationalist community caused the eruption in 1968. However, many senior figures in the Conservative party, such as Michael Gove, strongly opposed the thinking behind the Good Friday Agreement. They believed Tony Blair had given in to the IRA and many didn’t accept there was an Irish community entitled to equality of status and parity of esteem. Like the unionists, they insisted everyone in the north was British.

From the outset, David Cameron’s government adopted an entirely partisan approach, implementing a DUP wish list. The first disastrous decision was to accede to DUP demands to end 50-50 recruiting for the PSNI. That was one of the earliest actions of the now-disgraced former northern secretary, Owen Paterson, a man who provocatively wore a Royal Irish Rangers bracelet to show how impartial he was. The growing Catholic membership of the PSNI immediately stalled and has stuck at 32%, despite nationalists now being the largest community in the north.

Enda Kenny’s disengaged government remained silent. Worse still, Kenny allowed the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference (BIIGC) to lapse: there were no meetings on his watch. The Good Friday Agreement stipulates BIIGC meetings should be “regular and frequent”.

Leo Varadkar was no better. Even when the Stormont executive collapsed in 2017, he didn’t insist on a meeting, despite the main function of the BIIGC being to step in when the north’s institutions failed.

Obviously the most outrageous example of partisanship by the British was getting into bed with the DUP in 2017 after Theresa May’s disastrous election that summer. The confidence and supply arrangement that resulted in the calamitous Brexit treaty has DUP fingerprints all over it. The party’s single great hope for Brexit was that there would be a hard British border in Ireland, sealing off northern nationalists forever.

Jeffrey Donaldson

Challenged with the dire economic effects, Jeffrey Donaldson told the BBC he “could live with 40,000 job losses” – the consequence the NIO predicted. A hard border was the Holy Grail.

Since 2010 Conservative politicians have regularly expressed their support for the union, with several proclaiming their intention to campaign for it in a border poll. They adopted this position despite the GFA stating: “It is for the people of Ireland alone, by agreement between the two parts respectively and without external impediment, to exercise their right of self-determination.”

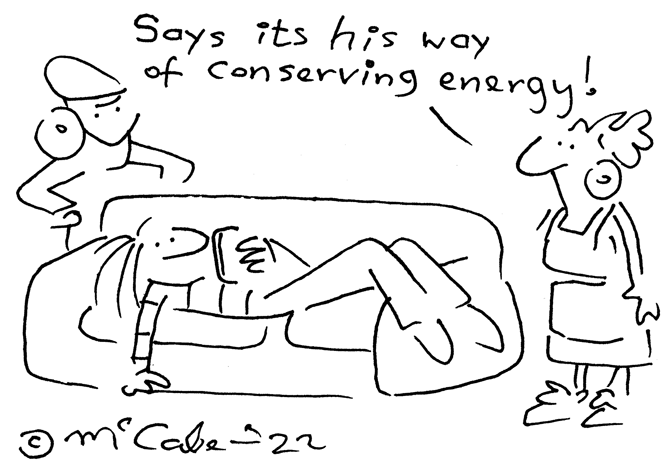

In 2021 Keir Starmer also stated his intention to campaign for the union until his advisers reminded him of the Good Friday Agreement obligations. No Dublin-based politician uttered a cheep.

In some ways even more serious has been the insidious extension of the concept of consent into a unionist veto on any change whatsoever. Varadkar made an unnecessary major concession at his meeting in the Wirral with Boris Johnson in 2019 when he agreed the consent of the Stormont assembly would be required for the continuation of the Northern Irish Protocol after 2024.

Yes, it would be by a simple majority of the assembly, but no consent was necessary because UK trade agreements are nothing to do with regional assemblies and these negotiations are between the UK and EU. However, the British were acting as partisan advocates for the DUP and Varadkar conceded. The DUP, with British support, is now demanding that ‘unionist consent’ is necessary for the protocol.

The critical point is that the British are supporting a minority veto, perhaps an inevitable development of their pro-unionist bias over the past decade. In the May assembly elections, a majority of parties elected support the protocol if tweaked and smoothed out to enable the north to benefit from both single market and GB trade. Businesses support that position. Yet the British government introduced the anti-protocol bill at the behest of the DUP, which has made its passage a condition for forming a northern executive.

This position adopted by the British have is completely incompatible with the Good Friday Agreement. It blatantly disregards the popular will in the north expressed in May. The British have allowed the DUP to expand the notion of the consent of ‘a majority’, required only for constitutional change, into anything the DUP opposes, like commissioning abortion services. The British are now supporting neither the will of ‘a majority’ nor ‘the majority’. They have got themselves into a position of flouting the GFA for the benefit of the DUP by bestowing on the declining DUP a minority veto.

Will the next demand be a minority veto on a border poll?

Given the shambolic state of the British government, none of these matters will be a priority for any minister in the near future. Indeed, the anti-protocol bill may founder. Still, it would be useful to hear an Irish minister’s views on these matters.