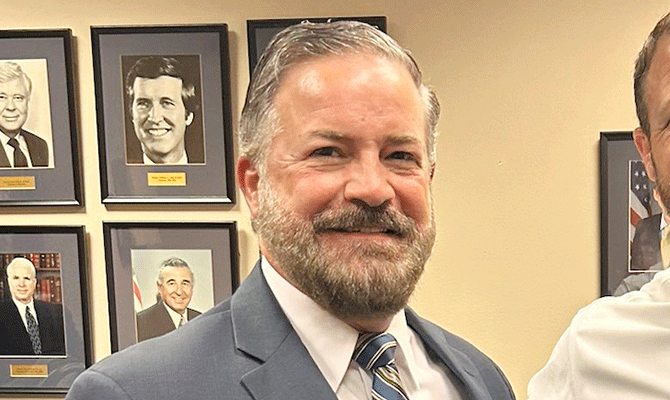

Tony Smurfit

NOW 60, it is gobsmacking that Tony Smurfit finds himself as the boss of the largest packaging company in the world, Smurfit Westrock, after pulling off a deal on a scale few thought him capable of. It is a bit of a head-scratcher though, given his pretty underwhelming performance as the very well paid CEO of the Smurfit Kappa Group (SKG) over a period of seven years.

Moreover, he has spent an awful lot of his time as a number two and seemed happy enough in the shadows to suggest that Tony was not destined for the very top. The question is whether his legacy will suffer the same fate as his father’s.

Certainly, Tony Smurfit is a patient man. He spent 17 years in SKG, from 1985 to 2002, shadowing Mick Smurfit, when his dad was calling the shots. Among the roles that have been held by Tony was chief executive of Smurfit Europe. He was heading for 40 at the time Mick sold out to private equity players Madison Dearborn in 2002 and took the group private, before stepping down as CEO (but remaining as non-executive chairman).

At that time, however, Mick clearly did not think his boy was ready for the top job and he was installed as chief operations officer, while Gary McGann, who had been chief finance officer, was installed as CEO over Tony’s head. The younger Smurfit then spent the next 13 years shadowing McGann, bringing to 30 years his time as a supporting actor.

This is a state of affairs that would clearly be intolerable for any truly driven and ambitious senior executive. And while Tony is clearly competent, he is far from an inspirational or visionary leader. Indeed, it is worth noting that Mick couldn’t stick being in the shadows of this own father, Jefferson Smurfit, and so jumped ship after just a few years to do his own thing in the UK. On foot of his success across the Irish Sea, Jefferson called Mick back to Dublin to take on the joint-MD role just five years later.

During the 13 years that Tony Smurfit followed McGann around, there was little to write home about, apart from a couple of moves. First, there was the only major move made by the company, the merger of Jefferson Smurfit group with Kappa Packaging in 2005 to create SKG and give the enlarged entity a bigger share of the European market.

This was followed in 2007 by the disastrous and utterly mistimed IPO to bring SKG back on to the stock market at a price of €16.50 a share. Those shares subsequently collapsed, hitting €1.20 in March 2009 after the market crash.

McGann and Smurfit did little over this period to address the void in SKG – the absence of a proper presence across the Atlantic, where all those giant US multinationals make their key worldwide packaging decisions.

When McGann retired as CEO in 2015, the SKG board – which had mainly been appointed by former chairman Mick Smurfit – would have been faced with little choice but to appoint Tony after his three-decade-long apprenticeship for the top job.

Given he had waited so long to become CEO, it was maybe not surprising that when International Paper (IP), the world’s leading corrugated box operator, came calling in 2018 with a golden opportunity, Tony baulked at the possibility of being bunked back down to number two.

Whatever the motivation, the reaction of Smurfit and his board to Mark Sutton’s €9bn take-over approach was aggressive and dismissive from the outset. Instead of thanking his lucky stars that the perfect US partner had arrived on his doorstep, Tony told the affable Sutton to take a running jump.

Whether the fact that the latter would have been in line to be the new group’s boss played any role in this decision we do not know and it is true that the Liam O’Mahony-chaired SKG board was emphatic that the IP proposal significantly undervalued the company. But that deal – which had led to an initial 31% bounce in the SKG share price – should never have been rejected and it is not surprising that there were questions asked by shareholders about the point blank refusal to engage with the Yanks.

It turned out subsequently that a bruised Tony felt let down by the government over its failure to send a signal of support, noting he was “surprised that, given the fact that Smurfit Kappa and its predecessor have been a significant economic and social contributor over decades, we had no message at all of any support from any direction”.

Having failed to do the tempting deal with the giant IP (and never having pulled off a deal of any real scale), Tony Smurfit bizarrely has now lashed out $20bn to complete a vastly inferior deal and acquire the WestRock packaging group in America, diluting his own shareholders by 49.6% in the process.

Michael Smurfit

LEGACY

Maybe Tony is now thinking of his legacy and, to have anything really worth talking about, SKG needed to fix the company’s strategic weakness by buying big in the US. WestRock found itself in the right place at the right time – vulnerable after having expanded too rapidly through acquisitions but still years away from achieving a balanced container board mill and corrugated box plant structure.

It should be noted that WestRock does have a huge non-cardboard packaging business, one in which SKG – and Tony Smurfit – have zero expertise.

The fact that WestRock was ripe for the picking does not mean, however, that the deal is the right one. Of course, Tony may surprise the market and reveal from behind the pedestrian front a business genius – which is exactly what Smurfit Westrock needs if it is to work.

What may be keeping him awake, however, and makes the task in hand all the harder, is the $8bn deal Mark Sutton has just pulled off by taking over the big DS Smith packaging operation, thereby moving IP right on to Tony’s European front lawn.

The new Smurfit Westrock combo is now the biggest packaging company in the world, an achievement that underscored the recent RTÉ hagiography on Mick Smurfit. Of course, the octogenarian tax exile had nothing to do with the deal, having sold what was the Jefferson Smurfit group to Chicago-based Madison Dearborn back in 2002 for €2.2bn.

That take-private was the first step in Tony Smurfit’s very long journey to be boss of the biggest packaging operation on the planet. At the time, Mick Smurfit came to an agreement with the private equity outfit, whereby he stood down as executive chairman and his then number two, Gary McGann, was slotted in as CEO.

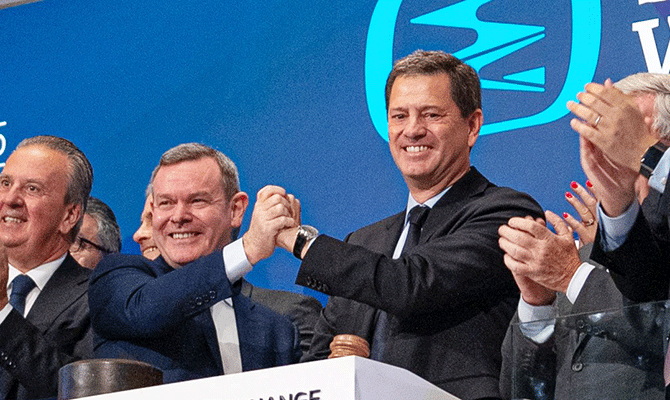

David Sewell

BIG SHOES TO FILL

Tony took a subsidiary role and McGann, presumably encouraged by Mick Smurfit, kept Tony close by during his 13-year reign.

Tony had big shoes to fill for sure – at least when it comes to his father – and Mick Smurfit was no man for downplaying his own qualities. After receiving an honorary doctorate in the mid-1980s, he insisted on being referred to as Dr Michael Smurfit, despite the fact that he had never even been to university.

Tony was himself awarded an hon doc earlier this year from his alma mater, UCD, but there is no sign of him adding the epithet to his bio. He was presented with the gown a couple of months after the completion of the merger with WestRock (“the latest distinguished chapter in the history of the group”), so he may see it as a form of vindication after those decades in the shadows.

According to the tribute from UCD dean Anthony Brabazon, Tony is “someone who has reshaped the industry at a global level” – just the kind of accolade Mick would love to have received as he continues his retirement is Monaco.

Of course, his son also happens to sport an address in the sunny tax haven – on Boulevard Princess Charlotte – despite having been CEO of an Irish-headquartered group for almost a decade. Pulling off that stunt is one of the things that Tony has in common with his dad. He has also shown signs of Mick’s ability to trouser vast sums from the corporate world, albeit on a lesser scale to date.

Having taken charge of the Smurfit packaging operation many moons ago, Mick moved into the big time in 1986, teaming up with Morgan Stanley to purchase a 50% stake in the huge Container Corporation of America for $1.2bn. Happily, the deal resulted in a nice $40m pay day for Mick.

In The Phoenix Annual 2000, Moneybags profiled the minted industrialist under the heading, “Smurfit: For God’s Sake Go”. This was based on the abysmal performance of Smurfit group shares, which from a peak of €2.05 in September 1987 had risen to only €2.13 by November 2000.

Furthermore, there was the little matter of the degree to which chairman and CEO Mick had enriched himself, earning around €150m over those 13 years.

What would have been far better (at least as far as shareholders were concerned) would have been for a recognised heavy-hitter to have taken the chair. For example, Peter Sutherland was chairman of BP and, based on the relationship between that company’s CEO and its profits, Mick Smurfit would have been paid £200,000 pa rather than £8m.

Mark Sutton

‘EQUITY IS BLOOD’

Having previously claimed “equity is blood”, he then pushed through a merger with Stone Corporation in the late 1990s that reduced the Smurfit group’s 46% shareholding in the US Smurfit Corporation down to 25%. There was also a series of related deals, including buying in a stake held by Morgan Stanley that cost $½bn and then buying out the rest of the US investment bank’s stake in Smurfit Stone at a further cost of a $550m.

Overall, Morgan Stanley actually managed to make almost $2bn out of its involvement in the Container Corporation of America buyout and the subsequent restructures in the years up to 2000, while the hapless Smurfit group’s Irish shareholders didn’t make a dime.

By the early noughties there was increasing tension with institutional shareholders on foot of the poor performance of the shares and the huge payouts to Mick Smurfit himself. In 2002 the Irish Association of Investment Managers pointed out that there had been “a total return to shareholders of approximately 2% pa since 1990”.

The £8m Smurfit trousered in 2001 created a furore and was probably the key factor in his arranging the €2.2bn takeout by Madison Dearborn in the summer of 2002. With the Smurfit family sitting on 8% and Mick Smurfit himself holding 6%, this deal saw him walk away with a tidy €132m and, at the age of 67, it suited him just fine to stand down as CEO.

Irial Finan

IP APPROACH

Roger Stone also retired and was replaced across the Atlantic by Ray Curran, while at home Madison Dearborn agreed for Gary McGann to take over as CEO, assisted by Tony Smurfit, who, eventually, became the boss himself.

For those who want to understand how Tony operates, the IP takeover approach in 2018 shines a revealing light. The €9bn price on the table put a value of €37.54 on the SKG shares – a dramatic 41% higher than the €26.60 these stood at the day before the first bid. Instead of biting Mark Sutton’s hand off, Tony (backed up by his chairman, Liam O’Mahoney) referred to a “highly opportunistic” approach that was never “even remotely acceptable”.

Mick Smurfit even threw in his own tuppenceworth, advising from Monaco: “At that level they wouldn’t get my shares”. This was despite the fact that by that stage any stake he held was so small that it was not disclosable.

The beauty of IP’s proposal was that it could use its dominant 30% stake of the US cardboard box business – where it served the bulk of the multinationals – and lever the deal into offering those multinational customers transatlantic packaging arrangements based on SKG’s 20% share of the European cardboard box market.

Both of the companies are fully integrated, with a balance of container board mills and cardboard box plants and so were nicely positioned to offer their combined customers international services on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as in South America. The deal would also have sorted out Tony Smurfit’s main headache – the lack of real exposure in the US and, therefore, access to the multinationals.

At the time IP came calling, SKG shares had been at their low pre-bid level because the big institutions had been losing faith, including the giant Norwegian state sovereign fund, which was selling down its 8.5% stake. Blackrock, which was the second-largest shareholder at the time, had been reducing its shareholding from 5.3% in 2016 to 4.2% in 2018, while GMT Capital took a more aggressive approach and flogged off the whole of its near 7% stake, as did Schroders with its 4% stake.

Whatever was behind Tony Smurfit’s strategy in snubbing IP, it is even harder to justify in hindsight given that WestRock is certainly far from being fully integrated and faces major rationalisation challenges, while there is also a significant chunk of its business that is outside the cardboard box sector.

With SKG having paid way over the odds for WestRock by offering €12bn in shares, the WestRock shareholders now have a 49% stake in the enlarged group, while Smurfit shareholders have inherited WestRock’s $8bn debt mountain.

At the same time, Sutton’s IP is moving into the European market courtesy of its takeover of SKG’s biggest rival in Europe, DS Smith. IP will now be able to offer its many US multinationals a transatlantic packaging option and will make Tony Smurfit’s business in Europe rather more challenging.

Incidentally, DS Smith is the company that brokered a plea deal in Italy to avoid a hefty fine for collusive practices, thus leaving SKG exposed to a €124m hit.

What will not go down well with SKG shareholders is that IP has agreed to an all-paper bid for DS Smith, whereby the latter will end up with 33% of the enlarged group’s equity. On a like-for-like basis, given that SKG is 20% larger than DS Smith in Europe, this suggests that Tony Smurfit was in a position to strike a deal with Sutton to give the SKG shareholders 40% of the proposed fully integrated enlarged group.

Moreover, if he played his cards right, Tony could have positioned himself as Sutton’s heir apparent and, given that the latter stepped down this year, the total wait would have been just five years.

That, of course, assumes that Smurfit would have been able to demonstrate to IP’s institutional shareholders that he has what it takes. It might be hard, however, to see them accepting a Monaco tax resident as group CEO.

There are some parallels here with Mick Smurfit’s proprietorial view of the company. When he came under intense pressure at the Smurfit group AGM in 2001 – both for the severe underperformance of the share price and his huge remuneration package – he told shareholders: “I’ll retire when I want to retire.”

Gary McGann was a good tactician but no strategist and, although he did a workman-like job running SKG for the 13 years to 2015, he paid little attention to the strategic weakness that was the US. There was little sign of urgency from Tony too but he clearly woke up this year, maybe as a result of turning 60, and hey presto, we have Smurfit Westrock.

WESTROCK

The American half of this sprawling new entity is in something of a mess, based around multiple acquisitions, the most significant being the €5bn purchase in 2018 of Kapstone Paper and Packaging.

The now departed CEO of WestRock, David Sewell, had been trying to fatten up his group in order to compete with IP but to do this has he had to buy unbalanced assets as well as ending up with businesses that were not within the main scope of WestRock.

The key to success in the packaging business is to ensure balance and vertical integration, with the huge container board mills feeding the various corrugation plants. Sewell had a big problem in WestRock on this front and, for example, his huge 645,000 tonne Panama City container board mill plant in Florida had to rely on outside corrugated box plants to buy its board, as WestRock does not have enough of its own box plants in the region.

Supplying outside box plants is a cut-throat business, so bad in fact that Sewell decided to close down the big Florida plant. For similar reasons, he also closed down a smaller 200,000 tonne container board mill that provided only 60% of its output to WestRock’s own plant. Two other plants were closed down for the same reason – the 510,000 tonne container board plant in Dacoma, Washington State, where 60% of output was shipped to third-party internal customers; and a 550,000 tonne plant in North Charleston, where 70% of output went to external customers.

These restructuring costs have been huge and ballooned from $410m in WestRock’s financial year to September 2022 to a whopping $2.75bn in the year to September 2023.

This has made it very difficult to decipher the company’s accounts. But, while the figures show huge losses at the bottom line, after stripping out the exceptional and impairment provisions, WestRock returned operating profits of $1.7bn in 2022 and, on a 5% reduction in sales in the year to September 2023, an underlying operating profit of $1.2bn.

BORROWINGS

The other big issue for WestRock is its huge net borrowings of $8bn, which cost $418m in interest charges in its last full year, such that the underlying $1.2bn operating profit ended up at only $800m.

In the US company’s most recent half-year results to the end of March 2024 – again excluding exceptionals – the underlying operating profit nearly halved to $351m on the back of a further 5% reduction in sales to $9.3bn – a run rate of $700m pa.

When you deduct $400m in interest, this gives an annualised performance pre-tax profit of $300m, making the $12bn in equity Tony Smurfit lashed out totally unsupportable – and that is before the $8bn debt that came wrapped up with a bow in the WestRock package.

A potentially serious problem too is that Sewell is not part of the new Smurfit Westrock management team, having stepped down after the deal closed in July. Given his extensive knowledge of all of WestRock’s plants, this makes no sense and clearly he should have been locked in as a key player for at least three years.

It is not only Moneybags who believes that the Smurfit Westrock deal is the wrong one. At the end of last year, hands-on fund manager Primestone Capital stated that Tony Smurfit should have embraced Mark Sutton, advising that this would have achieved “a transformational combination within International Paper to create an uncontested pure play global leader in corrugated packaging”.

Also of concern is that of SKG’s 23 mills in Europe, only eight have capacity over 400,000 tonnes pa – generally recognised as the minimum optimal size for a mill – and it has total annual capacity of eight million tonnes.

WestRock, meanwhile, is significantly larger, with 27 mills and annual container board capacity of 12.6 million tonnes, giving it a 463,000 tonne average mill size.

From his own base in Monaco, it is clear that Tony Smurfit has a real challenge on his hands in getting to grips with the nature and structure of all these plants across the US, never mind how to effectively implement the ongoing rationalisation programme inside WestRock, especially with former CEO Sewell now off the scene.

In effecting a $20bn reverse takeover of the troubled WestRock, at the same time that IP is taking over Smurfit’s biggest competitor in Europe, DS Smith, Tony Smurfit has landed his shareholders in a precarious position.

One of the so-called benefits of Smurfit’s reverse takeover of WestRock is that the new company, Smurfit Westrock, will have its primary listing on the New York Stock Exchange and that this might do for the new enlarged company what the same listing move has done for CRH and Flutter.

The problem is that, while there is massive depth to the Wall Street market, investors tend to mostly back companies with proven management, a coherent story and, more significantly, a progressive earning records. As Tony Smurfit did the wrong deal with the wrong company at an inflated price, this is not the ideal starting point.

If you take the experience of Carl McCann after the reverse takeover by Total Produce of Dole Foods, when he moved the primary listing to New York, then Smurfit Westrock shareholders could be in for bumpy ride.

It may prove slightly smoother for Tony Smurfit, now in situ as president and CEO, his sidekick Ken Bowles (executive vice president and group chief financial officer) and chairman Irial Finan, who have done rather well for themselves in recent times. Tony was paid a Mick Smurfit-like €10m over the last two years, while Bowles scooped €5.7m and Finan earns an impressive €354,000 pa for his non-executive role.

Mick Smurfit’s reign came to a sticky end, with shareholders berating him for the company’s poor performance and his hge personal rewards. Tony will be hoping he doesn’t suffer the same fate.

SMURFIT WESTROCK TODAY

Smurfit Westrock

IT PAYS to be careful when trying to interpret Tony Smurfit’s commentary on his company’s results and performance. As recently as March this year, when reviewing the 2023 results of Smurfit Kappa Group (SKG), the CEO observed: “Our 2023 results again demonstrated Smurfit Kappa’s proved capacity to perform across all market conditions.”

Given the very poor outturn, however, this claim simply does not stand up. Group sales actually fell 12% to €11.3bn and the group’s adjusted operating profit fell an even larger 16% to €1.4bn. Moreover, adjusted earnings per share were down a hefty 21% to €3.49.

Tony Smurfit did highlight that net debt had risen to €2.8bn – an inconvenient statistic that he manages to avoid mentioning when discussing the current quarterly results of the enlarged Smurfit Westrock group, covering the three months to the end of September 2024.

In these first figures from the enlarged entity, there is remarkably no attempt made to show comparative pro forma figures for the corresponding quarter in 2023. It is, therefore, impossible to make any proper judgement on the new group’s performance.

What investors have to make do with from Smurfit is: “I am pleased to report an excellent performance for the third quarter, the first for Smurfit Westrock.”

Net sales are shown at $7.7bn for the three months to the end of September but, while there is no pro forma comparison possible, the situation doesn’t look good given a net loss of $150m.

Smurfit attempts an explanation of sorts for the red ink, advising: “The net loss for the quarter of $150m was primarily due to the transaction-related expenses and purchase accounting adjustments totalling approximately $500m.”

If you examine the quarterly figures, “transaction and integration-related expenses associated with the combination” are shown at $267m, although there is also an entry for a WestRock stock write-off of $227m.

Even taking this $½bn expenses into account, it leaves the enlarged group with a net profit of $350m for the quarter. But there is no attempt made to calculate an adjusted earnings per share figure, which could be because the resulting 70c, on the basis of the buy-out share price of $51, is so poor that Smurfit thought better of disclosing it. This would put the shares on a pro forma annualised price/earnings multiple of 18 – a rating that could not sustain any further underperformance.

What is noteworthy about the absence of any mention by the CEO of the critical net debt figure is that in the past Tony Smurfit always highlighted this important statistic. It could be that the $13bn is simply considered too chunky to draw attention to, even though the scale of the debt is the very reason that it needs to be highlighted for shareholders.