Alan Curran

THE SAGA of the attempts by Barryroe Offshore Energy (BOE) to develop a huge oil and gas field off the south coast of Ireland continues to cause headaches and, utterly unsurprisingly, assorted legal eagles have now been called into the fray. This follows on foot of environment and climate minister Eamon Ryan’s refusal 10 weeks ago of BOE’s lease undertaking application (which is required by the company to proceed to the final phase development of the site, one of the largest undeveloped oil and gas fields in Europe). The decision of BOE’s largest shareholder, Larry Goodman, to seek the appointment of an examiner has staved off this week’s proposed liquidation of the exploration company but the hapless shareholders are no closer to drilling commencing and Ryan is now under the spotlight.

Reducing pollution from fossil fuels usage by switching to renewables is a necessary strategy but, in the short term, Ireland is currently using over 150,000 barrels of oil a day, all of which is imported – that is 55 million barrels of oil a year. On top of this, the country uses five billion cubic metres (m3) of natural gas, only 20% of which is now coming from the Corrib offshore gas field, with four billion m3 imported.

There is an associated pollution/energy cost associated with importing fuel, which would clearly be reduced if more of our energy was produced offshore Ireland (while also generating significant tax revenue based on the 25% regime now applicable). In this context, the Barryroe offshore discovery has an estimated 350 million barrels of oil recoverable and one trillion m3 of gas. To successfully develop this would therefore completely eliminate Ireland’s current dependence on Britain (now a net gas importer) for imports for most of the next decade.

It is therefore difficult for Eamon Ryan to justify applying the break to Barryroe, albeit ostensibly for reasons based on the financial capability of the consortium. Moreover, three years ago Leo Varadkar announced (in the US) the cessation of future oil and gas exploration offshore Ireland, although the Attorney General advised that existing licences would have to be honoured.

When rejecting BOE’s lease undertaking application in May, the Department of Environment, Climate and Communications (significantly it is not the ‘energy’ department) noted last November that the company had “not yet demonstrated sufficient compliance with the guidelines set out in DECC’s Financial Capability Assessment”. In the past, the Petroleum Affairs division was not known for demanding that such a level of financing was in place when companies signed up for exploration programmes.

BIGGER PLAYERS

The way it worked was that the firms involved would raise money having already secured their licences, sometimes actually having started drilling without the funds being in place. This would be followed by farming out the bulk of the development work to bigger players or raising funds through stock market placings.

The previous CEO – the underwhelming Alan Linn respectively exited back in October 2021, at which point James Menton took on the role of executive chairman until Alan Curran (who previously worked for Shell and Lundin Petroleum and oversaw the restructuring of Verus Petroleum) was appointed a year ago.

Menton then exited completely eight months ago at which stage British suit Peter Newman (with a background of working with the likes of Shell and the big UK Motor Fuel Group petrol forecourt operator) moved from senior independent director to chairman. Simon Brett also threw in the towel earlier this year to be replaced as CFO by Colin Christie, leaving only directors Andy MacKay and Ann-Marie O’Sullivan from the ancient regime.

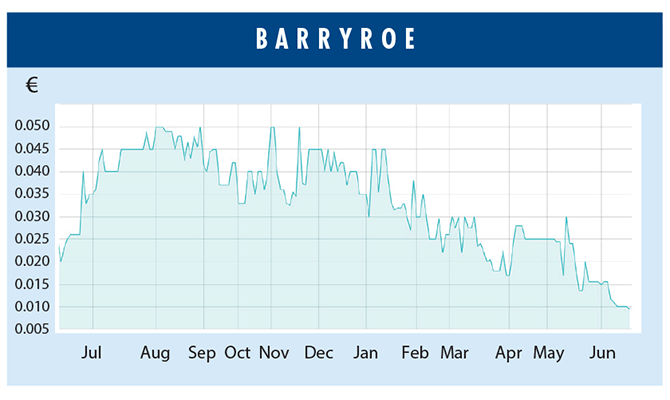

Newman and Curran sought to make some headway and proposed a two-well development programme that they hoped would force Ryan’s hand and greenlight the lease undertaking. Larry Goodman, surprisingly, committed to put up the full €40m budget. The minted beef baron had bought an 8% stake in BOE last year and doubled this when M&G flogged him all of its eight million shares at just 2c a share, crystallising a 90% loss in the process.

While there have been three gas fields developed offshore Ireland – Kinsale, Seven Heads and Corrib – no oil field has been progressed to the final stage. Barryroe was successfully drilled a few times in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, but the flow rates were no more than 1,500 barrels a day, each principally because the oil contained 20% wax that restricted oil flow.

UK exploration outfit Rockhopper, however, developed a rather simple device for overcoming this problem, by insulating the oil flow pipes so that the wax doesn’t congeal and restrict flow through the pipes. BOE partly used this technique in the winter of 2011–2012, when it last drilled Barryroe and flowed oil at the equivalent of 4,000 barrels of oil a day. If it had been fully insulated, it was estimated that the flow would have hit an equivalent of 6,000 barrels of oil a day.

On the back of this, the then CEO, Tony O’Reilly Jnr, raised what now looks like a remarkable €70m at a chunky €3.95c a share. Instead of using this to progress the successful Barryroe drilling, however, he poured the money into drilling holes in the very deep south Porcupine basin. (Barryroe is only 50km offshore Cork and in shallow waters of 100 metres.)

The Barryroe oil field stretches over 16km and in 2012 consultants RPS Energy were asked to carry out a more focused study on the central section of Barryroe, close to the 2012 oil discovery well. It confirmed that this section alone contains 83 million barrels of oil recoverable, which RPS estimated had a net present value, after recovering all development and production costs, of €392m based on a $70 oil price and €500m based on $80.

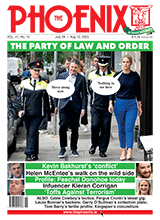

Larry Goodman

97.5% DISCOUNT

In this context, it is understandable why Goodman was tempted to put up the €40m to fund BOE’s development programme, although he insisted on harsh terms. BOE had to agree to issue his company, Vevan Unlimited, 107 million shares at 0.1c each, a whopping 97.5% discount to the then share price of 3c that would have increased his stake in BOE to a dominant 28% at a cost of only €107,000.

Most of the funding came by way of a €40m redeemable convertible secured note at an interest rate of 10% pa and conversion rights of 1.5c a share. If converted, these would have represented 73% of the total enlarged equity and dilute the existing shareholders down to 27%. Goodman would then have ended up with over 80% of BOE’s total equity.

Newman and Curran arranged a €20m placing at the same 1.5c a share, offered to all BOE shareholders, thus at least allowing them the opportunity to limit the extent of their dilution, but also to improve the financial health of the company.

Before this placing progressed, Eamon Ryan’s department confirmed on May 19: “From a technical perspective, the Barryroe lease undertaking application is satisfactory for the purposes of Section 3 of the 2007 licensing terms and the technical capability of the applicants is satisfactory for the purpose of Section 9 (a) of the Act of 1960.” Ryan was, however, “not satisfied with the financial capability of the applicants… and cannot grant the lease undertaking as sought”. (In the department’s opinion, as advised by independent consultants, BOE required net assets that represented 3.5 times the cost of the proposed.)

It has since been left to Larry Goodman to kick off the litigation that was inevitably set to follow Ryan’s decision. While, on the surface at least, the Barryroe management had adopted a strategy of rolling over and winding up the company, Goodman has petitioned the High Court to have an examiner appointed, with the process unlikely to be properly progressed until October. Separately, BOE’s 20% partner in the Barryroe project, London-registered Lansdowne Oil & Gas, has raised £200,000 to help it progress its legal claim against the state under the Energy Charter Treaty, a controversial international agreement designed to protect energy investors.

This story clearly has a long way to run yet and could end up costing the taxpayer a pretty penny. Ryan could well be called upon to justify his department’s approach to the Barryroe oil field, which currently looks to have verged on reckless given Ireland’s dependence on imported energy.

Reference the Market Abuse Regulations 2005, nothing published by Moneybags in this section is to be taken as a recommendation, either implicit or explicit, to buy or sell any of the shares mentioned.